NORMAN — One hundred and seventy-two years ago she would have marched with Elizabeth Cady Stanton or locked arms with Susan B. Anthony.

Had she been around then, she would have been a source for Nellie Bly or raised cain with Ida Tarbell.

Small, feisty and the holder of the gold standard for stubborn, Norman political activist Mary Francis seems almost out of place in modern society. The former school teacher, now with a touch of silver-gray in her hair, always seems to be asking questions – questions she keeps asking until she gets an answer.

Diminutive and, at times, grandmotherly, Mary Francis has leveraged years’ worth of political connections, mastered the concept of the non-violent protest and developed her own unique form of bipartisanship to rattle cages, twist arms and push her agenda.

But she didn’t set out to become a political activist.

She just sorta painted her way into it.

And today, at 77, she has no plans to stop. Today, Mary Francis is still advocating for those who don’t have a voice and for changes that, she believes, would make the planet a better place.

Her opponents call her a troublemaker.

They’re right.

Studying art, Dr. King and learning how to protest

She was born in southeastern Oklahoma, in LeFlore County. She graduated from high school at the tiny town of Howe, a wide spot in the road just off US 59. She was timid and quiet and liked to read. Life was about getting married and having babies.

“I grew up as a passive child who read books all the time,” Mary Fancis said. “It was totally understood that girls were going to get married and have babies. You never said ‘no’ to a grown-up, you never lied and you never complained.”

She didn’t go on her first date until she was 17 and it took some arm twisting to get that done. But once she received the blessing from her father, Mary began dating Joe Beaver, a student at the University of Oklahoma.

Exactly one year and two days later, she married Joe and moved to Norman.

Norman was a different world from southeastern Oklahoma. At OU, she herself became a student even though she wasn’t quite sure what to study. She liked art and she was good at math, but the decision about her major field of study remained elusive. It took a no-nonsense adviser to get her started.

“I went to the professor who was going to be my adviser and he said, ‘okay what are you good at?” she said. “At that time I was scared. I was from the cornfield, this passive little girl. I said, ‘well I’m pretty good at art and math.”

The professor made the decision for her.

“Okay,” he said, “we’re going to put you in the art school.”

Still, she remained unsure. “As he started to write things down, I had the temerity to say, ‘I really like math,’” she said. “He just kept writing and said, ‘well if you flunk out of art school, we’ll look at math.’”

That decision would prove fateful.

During her senior year, one of her paintings won the Eight State Art Award (now known as the Southwest Art Award). That painting, entitled Miss Integration, was displayed at the Oklahoma Art Center, a featured attraction at the state fairgrounds.

At least, it hung there for a while.

Then all hell broke loose.

Shortly after the exhibit opened, members of the board of trustees of the Oklahoma Art Center ordered several of the paintings, all of which featured nude figures, removed. Francis’ work was harshly criticized but remained displayed.

Stories published at the time, noted that the show’s curator, Patric Shannon, defended the works saying the paintings, “were removed against professional protest and the advice of the director.”

For Mary Francis, the turmoil was life changing.

“The Baptists who were on the board saw it (her painting) and they were incensed,” she said. “They insisted that it come down. They actually took down two other paintings. But Shannon refused to let them take mine done.”

The incident was the first skirmish in what would become a lifetime of battles for her – battles which would cover the political and cultural landscape. The fight over her art would change her. It would help shape her views on politics and religion and, over time, mark her for a different calling.

Even though she lost the battle over her art, she came out ahead — she kept the painting and donated it to the Women’s Resource Center. “I got it back,” she said. “I told him (Shannon) that I don’t want my painting to be under the purview of a board who wants to take it off the wall.”

The activist in Alaska

Though her tenure in art school opened doors for her career, Francis’ four years in Norman also brought about great personal change – some of it painful.

Just before her senior year at OU, in 1964, she and Joe divorced. “He was a good man, but he was immature,” she said. “The art school will change you.”

At OU, Mary Francis joined the Student Democratic Society. She became interested in Dr. King’s issues in the south. Studying art, it seemed, had opened her eyes to social issues.

“Dr. King was my hero,” she said.

But Oklahoma wasn’t the right place for her, so she headed far north – to Alaska.

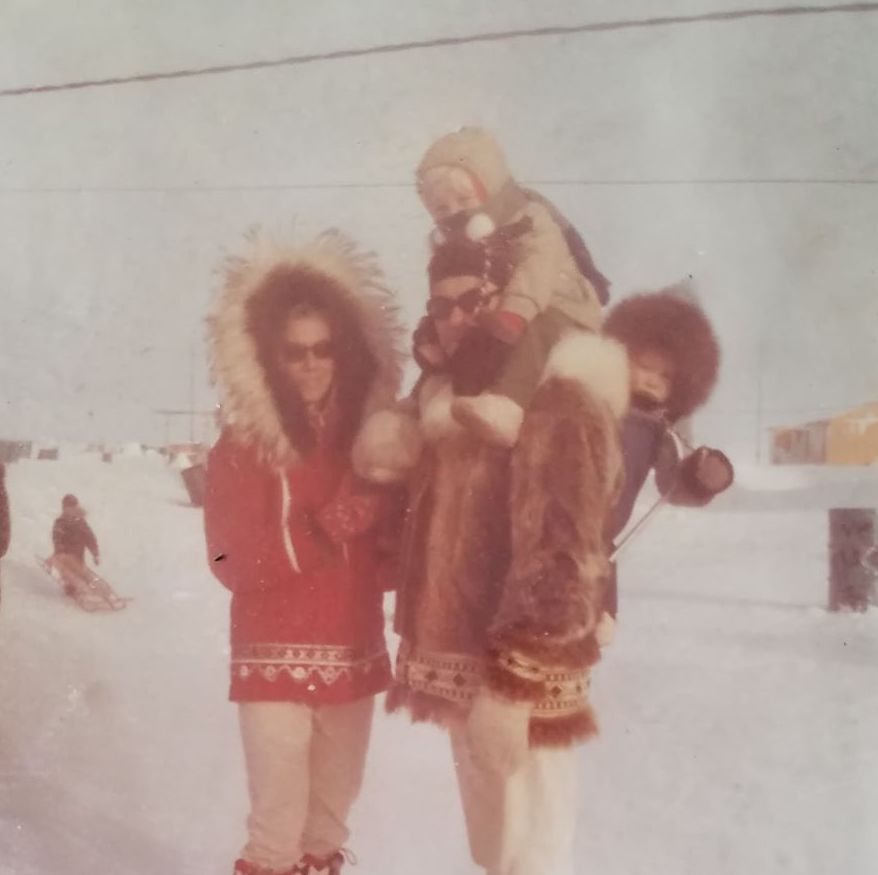

By the late 1960s, Mary Francis had traded red dirt for perpetual cold and found herself teaching Eskimo children in the small villages near Nome, Alaska. She married again, this time to the man who she called the ‘love of her life,’ Dick Francis.

She became a mother, raising two small boys and, once again, found herself in trouble.

“I spent about 10 years teaching in little Eskimo villages,” she said. “I also circulated some initiative petitions because of what happened to the children from the small villages.”

Those kids, she said, were forced to leave their village and attend high school in Nome. Because the children were young, and often the trip was their first time away from home, they were easy targets for abuse.

“These were children had never been outside of their village. They were so lonely. They had never been away from mom and dad and so they were easy victims,” she said.

Mary Francis said the director of the school would go into the bars at Nome and get young, underage girls off barstools and take them back to their school dormitory. At that time the bars were open around the clock.

“We would find little 15-year-olds being served alcohol,” she said.

To fight the problem, Mary Francis said she partnered with the town’s ‘arch Republican’ and circulated an initiative petition that would close the bars during specific times during the week and on weekends to prevent minors from being served alcohol.

The idea seemed like a good one – until she had her life threatened.

“I walked into the barbershop with my clipboard,” she said. “The bar owner, a man named Jim West, frowned and said, ‘Mary Francis you are circulating that damned petition!”

I looked at him and replied, “Well, yeah Jim, you want to sign?”

Instead of signing the man told her, “you’re gonna mess around and get your house burned.”

It was at this point, she said, that she realized her life – and those of her family – could be in danger. “I had two small children at the time,” she said. “That was a scary thing to me.”

Mary Francis turned to leave, speaking to West a second time. “I said, ‘well I guess that means you don’t want to sign my petition,” she said.

Later she went home and told her husband to never ask her to stop circulating the petition. “Instead, he went to Anchorage got two chain link ladders and taught the kids how to escape the house via a ladder. We made a game out of climbing up and down the stairs with the boys.”

She would remain in Alaska until the late 70s teaching, causing trouble and honing her ideas about social justice. But Mary Francis didn’t stay there. Her personal life in turmoil, she returned to the place she loved best, her adopted home – Norman.

A return to the Land of Red Dirt

Back in Norman, she had the chance to catch her breath and to end her marriage.

“I came back to Norman and got a divorce,” she said. She said her husband’s struggle with alcoholism and incidents of domestic abuse fractured their home. “He started drinking. When he drank he got mad and got jealous. I said that was not going to happen in front of my kids so I left.”

She also went back to OU, earning a Master’s Degree in Education and certification as a reading specialist. In her spare time, she studied Chinese calligraphy.

And once again, she jumped into politics.

After joining the Unitarian Universalist Church, she and several others began pushing the Norman City Council for a provision that protected the LGBT community from discrimination in housing and employment.

Mary Francis and her group initially met with success. In October of 1983, the Norman City Council adopted an anti-discrimination ordinance 7-2 on first reading. But a month later, the ordinance failed.

“We pushed the city for LGBT protection,” she said. “That was in the 80s and it was killed.”

But the work was far from over. After serving a six-year term on Norman’s Enforcement Authority, the forerunner to its Election Commission, she became the state vice chairman for Common Cause, a non-partisan activist group.

And it was there, as the number two person in a statewide group, that she perfected her hell-raising ability.

Acting with the help of then-Governor Henry Bellmon, a Republican, Common Cause became a major player in the governor’s Constitutional Revision Commission. That group was tasked by Bellmon with revising and streamlining Oklahoma’s cumbersome state constitution.

“They asked us, ‘what does Common Cause want?” she said. “We said three things: A change in Article 10, the executive branch; a change in Article 17, which addressed county commissioners and we wanted a new article – an ethics commission.”

They scored on one of the three.

Working with Andrew Tevington, Bellmon’s attorney, and Robert Henry, who was attorney general at the time, the group hammered out language which created the Oklahoma Ethics Commission.

“We met every damned Saturday,” Mary Francis said. “But Andrew was awesome. The ethics article passed and it was basically, Andrew’s writing.”

Though the other articles didn’t pass, for Mary Francis the effort was worth the lost weekends. And yes, her work ruffled the feathers of many state lawmakers, but she didn’t care.

“You have to understand that once she gets involved in an issue, she doesn’t stop,” said former Oklahoma Senate Pro Tempore, Cal Hobson, a Democrat. “Mary Francis is tenacious. She’s focused and she doesn’t quit.”

Hobson, who has found himself on both sides of an issue with her, said Mary Francis is one of those people who take their activism seriously. “We haven’t always agreed but I have the utmost respect for her,” he said. “When she is involved she approaches the problem like a bulldog – she bites on and doesn’t let go.”

Still, over the course of her long career, she has won more than she lost.

Lessons in non-violent civil disobedience

Ask almost any seasoned activist and they’ll tell you that activism comes with risks. That’s certainly true for Mary Francis.

A well-seasoned protestor, she has – on four occasions – found herself arrested and in handcuffs. The first incident occurred in 2005, just after President George W. Bush ordered the bombing of Iraq.

Reappointed to another term on Norman’s Enforcement Authority, Mary Francis immersed herself in Norman politics. She also began following political activist Cindy Sheehan and the activist group Code Pink. When Code Pink to traveled to Washington, D.C., to deliver a signed petition against the war to the president, Mary Francis went along to help.

Well, at least they tried to deliver the petition.

“They refused accept them and we refused to move, so we all got arrested,” she said.

Her second arrest occurred in 2006, when she was taken into custody in Duncan with 15 others after they protested outside a Haliburton shareholders meeting. That arrest, Mary Francis said proudly, came at the request of Vice President Dick Cheney.

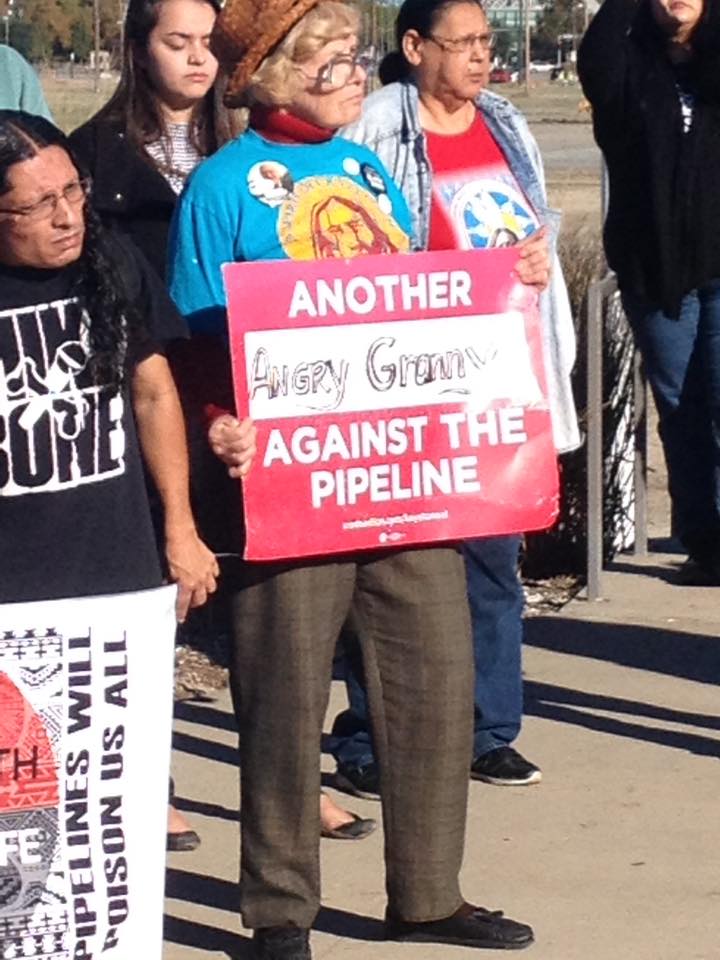

The third time came in 2011, this time over the Keystone Pipeline.

That pipeline incident, she said, was part of a coordinated effort to put pressure on President Barack Obama to address the pipeline. “About 1,200 of us were arrested then, over a period of two weeks,” she said.

Because Obama had ‘never said the words Keystone Pipeline’ the group 350.org hoped to place the issue in front of the president by having the membership continuously arrested. With those arrests appearing regularly in the news media, the group assumed – correctly – that their arrest would get the president’s attention.

“He was the only one who could authorize the pipeline moving across the border,” Mary Francis said. “We were determined to bring this to the mainstream media’s attention and put this on his (Obama’s) plate.”

Responding to the call, thousands went to DC and were arrested. They paid their fines out of their own money. The media caught on and the president ‘got the question.’

“Sure enough after two weeks, after arrest after arrest after arrest, somebody on Air Force one asked Obama ‘what the hell is going on with the Keystone Pipeline and all those arrests?’ And he had to talk about it. It went viral. We were a success.”

Her most recent arrest, the fourth, was on 59th Street in New York in front of a breakfast meeting that included President Donald Trump. “The officer was very respectful,” she said. “We had a nice conversation. He told me all about his family.”

For those who pay attention to history, her arrests shouldn’t come as a surprise, they are taken directly from Dr. King’s playbook on non-violent civil disobedience

“Civil disobedience takes time,” she said. “But you still gotta do it. You still gotta do it.”

That time she started her own radio station

As an activist, she hadn’t planned on founding a public radio station.

She sorta got talked into it.

And somehow, during the fall of 2007 that’s what happened. After a friend from Houston, Teresa Allen, pulled her into a conference call about broadcasting and licenses from the Federal Communications Commission, Mary Francis found herself committing to a project she never saw coming – creating a public radio station.

“(Teresa) was involved with the big Pacifica station in Houston,” she said. “She called me up and said the FCC had a license opening and that I needed to apply.”

Mary Francis wasn’t easily convinced, but her friend, she said, kept insisting and before long, Mary Francis had committed.

“I guess the thing that got me was discovering that 80 percent of the public radio station licenses had been snatched up by the religious right,” she said. “They jumped in and figured out they could talk to the world if they had one of these radio stations. They snatched them up.”

Progressives, she said, missed out.

“That incensed me,” she said.

Looking for more ‘balance’ in the public airwaves, she dipped into her savings and got help from attorney Mike Couzens who had worked at the Federal Communication Commission. Before long they had completed and filed the application.

But Mary Francis didn’t want to be a media mogul. Instead, she asked Norman’s Unitarian Universalist Church to be the non-profit on the license.

“I talked to the board and they agreed,” she said. “So I kicked in $3,000 and we did it.”

The application was filed for the license in October of 2007. The process was finally completed in 2017 and KVOY went on the air on Jan. 7th, 2017 after a decade of fending off competitors. Three years later, the Oklahoma wind would take down her tower.

“It was ten damned years,” she said. “But we’re not done.”

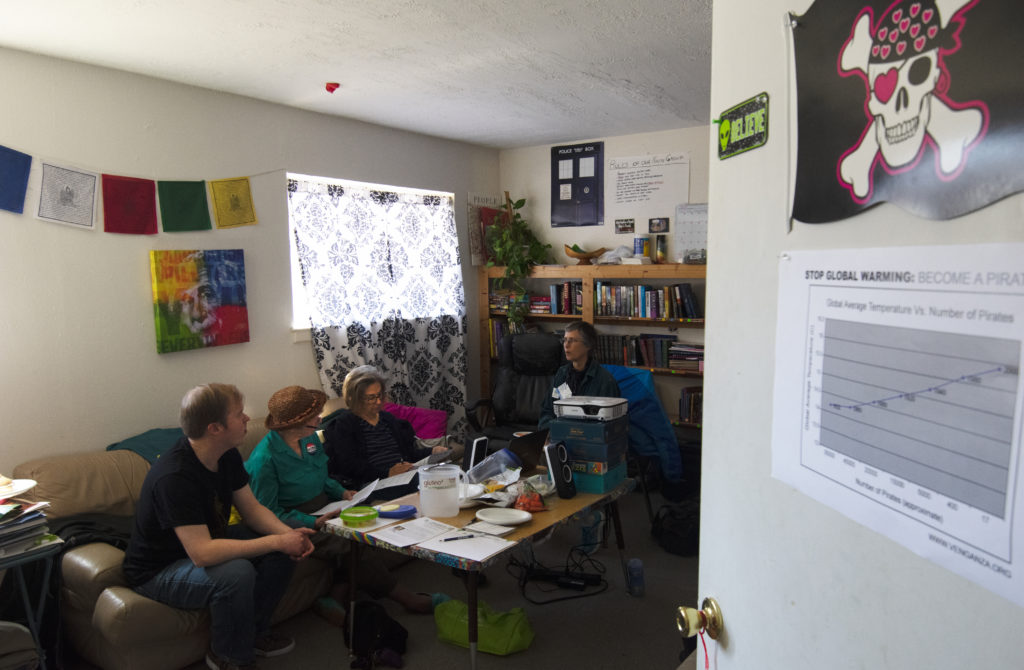

An advocate for the Earth

The room is small, cramped. Filled with books, it’s illuminated by two small windows with curtains the size of bed sheets. Posters cover the walls. A cute, pink and black skull and crossed bones flag – complete with a heart-embossed du rag – hangs on the door.

During the week, it’s the library for Norman’s Unitarian Universalist Church. On this particular Saturday, the room serves as the headquarters for the Norman Citizens Climate Group.

Five members are in attendance today. They are smart, well-spoken and organized. The agenda includes a video conference with Bob Inglis, a former Republican Congressman from South Carolina and now the executive director of republicEN. That organization, Inglis said, is “devoted to persuading conservatives to address climate change with market based solutions.”

Mary Francis, sporting her large ‘vote’ button and a bowler hat made of cedar strips is ready. Today the group is planning for future events and developing ways to raise awareness about environmental issues.

For them, the agenda is crowded and time is short.

“Every year we go to Washington DC. We’ve been working on a plan,” she said.

Part of a multi-nation network, the Citizens Climate Lobby travels to Washington, D.C. every year and attempts to speak with all 535 members of Congress. Their goal is to put together a bipartisan coalition to address climate issues.

Their plan would establish a fee which would be assessed on every fossil fuel company. However, instead of the money going to the government, the fee would be redistributed back to the general public. That payment, which would amount to about $60 per person per month would more than offset the increased fuel costs, she said.

“We had a study done and it showed about 70 percent of the public would come out ahead,” she said. “The money from the fee would flow through the IRS and a monthly check would be sent to each taxpayer.”

So far, the group has had some success. A bill — HR 763 which is based on the Citizen’s Climate Lobby plan — has been introduced in Congress and across the country, more people are speaking of the need to address climate change. But for Mary Francis and her group, that’s not enough.

They have emails to write and plans to make. This year is the 50th anniversary of Earth Day and you can bet that the Norman Citizens Climate Group will be there.

“I don’t think we have much time to fix this,” Mary Francis said. “I think we only have a few years. I am afraid our biggest failure is yet to come but it doesn’t stop us from trying to fix it.”

Fighting the good fight

Though she’s helped change the Oklahoma Constitution, pushed for LGBT rights and continues her fight against climate change, Mary Francis will acknowledge that not everything she has done has been a success.

Some of her ideas have been shot down and on more than one occasion, she’s lost a battle — but it’s not within her to quit.

Not even when the failure is painful.

“She won’t stop. She doesn’t quit,” said former Norman City Councilman Bill Hickman. “She latches onto an issue and doesn’t let go.”

Like Hobson, Hickman uses the same word to describe Mary Francis’ efforts: bulldog. “She sinks her teeth into an issue and she gives it everything she has,” Hickman said. “I really respect that.”

Still, Mary Francis will readily acknowledge that her efforts have come with costs. Her biggest failure, she said, was not being able to stop her husband’s drinking and not spending more time with her children. She speaks tearfully about sending her boys to spend the summer with their father, then crying when they were gone.

“You don’t get over that loneliness,” she said. “The loneliness of being without your kids.”

And though the relationship with her boys is strong and solid, the biggest regrets of her life are confined to home. “I missed out on many things with my boys,” she said. “I was so busy.”

She’s still busy.

In between the trips to Washington D.C., her efforts at the state Capitol and her handprints on Cleveland County politics, Mary Francis is working to train the next generation of activists. She gets excited speaking about groups like the Sunrise Movement, and teenagers such as Greta Thunberg.

She’s also worried. About the climate, the Earth, the kids of tomorrow and her fellow humans. She needs more time and she needs more like-minded people.

Good hellraising, you see, has to be cultivated and encouraged.

“The young people are organizing,” she said. “I keep telling people, stay back, let them do it. The Sunrise Movement are the ones who sat in Nancy Pelosi’s office for several days to force her to talk about climate change. The are the ones who are protesting and getting arrested. They are the ones who are going out there and raising hell.”

Young people, she said, are the country’s only hope. “If anyone is going to stop this crazy stuff it’s going to be them,” she said.

Just like Stanton, Tarbell, Anthony and Bly, Mary Francis wants to leave the world in better shape than she found it. But, at the same time, she wants the world to listen to its women. She wants the world to know that women were not just put on the planet to get married and have babies.

Women, she said, should make their voices heard and not be afraid to cause a little trouble.

“I didn’t make all this trouble,” she said. “It just shows up. I didn’t cause it. I’m trying to fix it.”