(Author’s Note: The period between 1890 and 1910 was one of the most unique and dynamic in Oklahoma history. Not only did the Twin Territories merge to become a state but Oklahoma’s Constitution was written and adopted. After the Constitution’s passage, then-President Theodore Roosevelt signed legislation making Oklahoma the 46th state of the union. But other events — which weren’t so positive — also took place, including an incredibly racist gubernatorial campaign and the development of onerous legislation that disenfranchised thousands of African American and Native American residents. These stories explore this period and are based on documents, written first-hand accounts and other resources obtained from the Oklahoma History Center and the state’s official archives. In light of recent events and the nationwide call for racial harmony, we believe these stories provide much deeper context for the state’s often troubled racial history. This is the four story in a multi-part series.)

•

At first glance, Governor Charles Haskell’s election victory and his effort to move the capital seemed overwhelming and decisive. But documents show the petition’s success was the result of something other than a public vote: a possibly well-planned and organized case of election fraud.

Consider this: After the petition had been circulated and the election date set, Haskell changed the election date from Tuesday to the previous Saturday – quite possibly the only time in state history that a statewide election was not held on a Tuesday. By choosing the Saturday date, Haskell knew no court would be open and opponents of the petition would have to wait a full 24 hours before they could file a lawsuit. The date change, echoing an earlier time when Haskell used the same strategy, was an attempt to prevent residents from seeking help from the judiciary.

Haskell’s sudden change to the petition – scratching out the Tuesday date and writing in the new one – probably violated state law, too, because the change came after the petition was certified and the date had already been set by the attorney general.

Critics of the Capitol’s move pushed back against the governor’s action. Letters archived at the Oklahoma History Center show that representatives from both Guthrie and Shawnee – two of the three sites listed as possible locations for the capital – wrote to Haskell expressing serious concerns about the initiative petition and the legal process used by the governor to locate the capital.

The letter from the Capital Location Campaign Committee of Guthrie, said the people of the city, while desiring the capital, “would not want to be the beneficiaries under a measure so coupled with dishonor, so devoid of any protection of the interests of tax-payers, so manifestly unfair to other cities of the state, shutting out, as it does, all but three from competing for the high honor of being the capital of the state and contemplating the location of all state institutions at the capital to the detriment of many other communities.”

A subsequent letter, from the Shawnee Capital Location committee, questioned the governor’s authority to move the capital. “Your connection with the framing of the bill and your announced support of its provisions leads us to believe that your option proposition was not submitted in good faith and that will be will not be carried out in spirit or in letter.”

Those efforts, coupled with the fact the previously ‘unknown’ petition was circulated by men who worked for the Oklahoman newspaper and who were, somehow, able both to deliver newspapers and quickly collect and validate signatures at the same time, raises a number of legal questions about the veracity of the petition itself and those signatures that placed it on the ballot.

Even today no documents could be found that show whether the individual signatures were ever examined and certified by any official of the Haskell administration. However, court documents –– filed immediately after the petition was ‘officially certified’ by Cross’ office –– raise questions about the veracity of the petition and those who signed the document.

Attorneys for Guthrie noted that many of those who signed the document were not legal residents of Oklahoma, were underage, or were women (who could not vote at the time).

And then there were the election returns.

While most historians agree that about 160,000 Oklahomans – all white men, because neither African Americans nor women were allowed to vote – cast their ballot in the election, the method and the way the ballots were canvassed and counted, indicates that Haskell probably had advance knowledge of what those returns would be.

In the book, The 46th Star, Haskell said that he and his wife went home to Muskogee on Friday, June 10th so they could vote. On Saturday after voting, the couple traveled to Tulsa to attend a dinner at the Brady Hotel, hosted by Tulsa’s commercial club.

“We reached Tulsa during the day and were there from perhaps four o’clock in the afternoon until midnight,” Haskell said. “Of course, by the close of the eleventh the battle of the ballots was over.”

During the banquet Haskell asked Tate Brady, owner of the Brady Hotel and a close advisor to the governor, to track down election results. “Brady,” Haskell said, “had been wonderfully effective in getting election returns.”

But how?

While both the telegraph and telephone existed in 1910, the idea that all 160,000 ballots could be counted by hand, inspected, and then shared via telephone or telegraph with Brady seems doubtful. Further, Haskell told Hurst that he had the actual numbers of those who voted – supposedly gathered by Brady – all by midnight Saturday, without seeing complete election returns.

“He (Brady) had a list of a vast majority of the precincts in the state which showed 98,000 plus for Oklahoma City, 24,000 plus for Guthrie and 7,000 plus for Shawnee. It was almost a complete precinct return,” Haskell said.

How Brady, using 1910 technology, was able to gather such a complete list of election returns by midnight of the day of the election remains a mystery. Records show that in 1907 the entire state had only 715 telephone systems – commercial, mutual, independent farm and rural lines, which would have made it virtually impossible to ensure that all the election returns from every voting precinct could have been obtained by midnight.

The most probable answer points to a time-honored tradition: stuffing the ballot box or falsifying election returns.

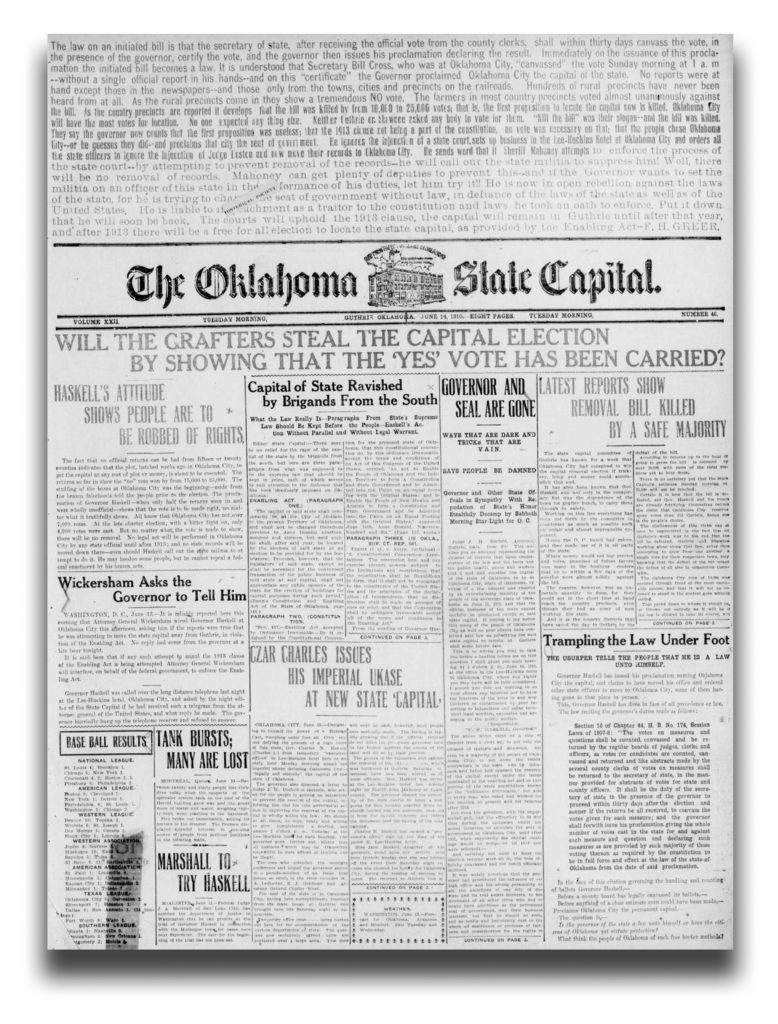

The Daily State Capital first raised election fraud concerns in an above-the-flag editorial the day after the election, in its Sunday, June 12, edition. “In the vote on the election Saturday, the estimate is about 150,000 votes were cast,” Greer wrote. “Of these about 50,000 have been unofficially reported. Of these there is a majority of about 5,000 against the removal of the state capital.”

Oklahoma City’s vote, Greer said, was 13,192. “Of course, it has no such number of votes,” he wrote. “It cast about 4,200 votes at the last charter election, when a very bitter fight was won.” Greer said Oklahoma City’s vote included “not less than 5,000 to 7,000 stuffed ballots” and “anything like official returns cannot be had before Monday.”

In a Saturday evening Extra Edition of the Guthrie Daily Leader, Haskell’s own son-in-law, publisher Leslie Niblack, also questioned validity of the election in the June 14 edition.

“Lack of Registration Permits of Large Fraudulent Vote,” a headline in the Daily Leader screamed, adding that “Committees Visit Hotels and Guests are Urged and Cajoled to Vote.” Another headline charged that ‘Hogtown’ was “stuffing (the) ballot box.”

The story, by reporter Siloam R. Bennett, told of how “hotel guests were accosted, men of one hour’s acquaintance were besieged to cast their ballots and the city was wholly in the hands of those seeking to secure removal of the state seat of government.”

Great sums of money, Bennett wrote, were in circulation on Saturday as were flyers that carried the message that “you don’t have to be registered to vote for Oklahoma City.”

Niblack’s paper, just two days later, would again charge the election was fraudulent. “Under the returns as now, allowing Oklahoma City the fourteen thousand votes cast, eight-thousand of them by non-voters, the ‘no’ side has a clear majority. State law required the vote to be canvassed in Guthrie,” he wrote.

W. F. Kerr and Ina Gainer’s book, The Story of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma The Biggest Little City in the World, also hints at election irregularities, noting that “strategy and treachery and acrimony were indulged in to an extent by all three of the applicant cities.”

That treachery, in some areas, was racial. In Guthrie stories were published that claimed African Americans sent telegrams to residents in Oklahoma City urging residents to vote for Guthrie, in the hopes to drive racist to the polls.

“One of the stock crimes of the grafters in the capital location campaign has been that the Negro vote would be for Guthrie,” the Daily Leader reported. The telegrams, which said “Vote yes on bill; Vote yes for Guthrie were signed, Rev. Page. “This is palpably an effort to use the name President I.E. Page of the Colored and Agricultural Institute, Langston, in an effort to secure votes for Oklahoma City,” the newspaper said.

It’s doubtful the flyers were a legitimate attempt to get minorities to the polls. Instead, by publishing handouts that supposedly encouraged an African American vote, opponents of Guthrie’s effort to hold on to the capital hoped the flyer would spark the area’s white supermacists to action.

•

The change in atmosphere regard races was, in part, due to actions by the Territorial Legislature under the leadership of William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray and Governor Haskell. Those acts, including the ‘Grandfather Clause’ bill had made it illegal for African Americans to vote unless they could prove their ancestors, too, had cast ballots. Haskell’s disdain for African Americans and their Republican benefactors was already well known.

The State Capital and the Daily Leader’s complaints were underscored more than a half century later when former Oklahoma City manager Albert McRill wrote a tell-all book about early life in Oklahoma City. McRill’s book, And Satan Came Also, charged that Oklahoma City used election fraud in the removal election by organizing a homeless encampment on the riverbank to stuff the ballot box during the relocation election.

In the book, McRill told the story of Larry Reedy, a small-time prizefighter from Chicago’s Loop District, whose specialty was rigging elections. During the time of the removal petition Reedy served as an ‘inspector’ for one of Oklahoma City’s largest voting precincts.

“Larry never started out on a ballot-stealing mission with greater zest or stronger purpose,” McRill wrote. “Never before had he been enlisted in a ‘great moral crusade’ with such tremendous possibilities.”

Reedy’s first contact, McRill said, was with a 1,000-member strong homeless settlement on the North Canadian River, called the ‘Hobo Roost.’ “Election day came,” McRill wrote. “Recruits from the ‘Hobo Roost’ and the tenderloin outdid anything Precinct ‘A’ had ever done…with a motley crew of strange, bewhiskered sojourners surging in and out of the polling places, clamoring for ballots.”

Reedy’s precinct, McRill wrote, cast 1037 votes for Oklahoma City and only seven for Guthrie. “He (Reedy) was acclaimed the ‘hero of the hour,’ and strutted along the streets, receiving the plaudits of eminent citizens,” McRill wrote.

Hurst’s book on the history of the state’s constitutional convention, provides yet another clue. Hurst wrote that during the 1907 election to approve or disapprove the state’s constitution, (the same election which saw Haskell elected governor) canvassed returns showed 180,333 votes for the constitution to 73,059 against approval – a total of 253,392 votes.

Election returns show the Constitution’s official vote canvass required nearly six weeks to complete. In contrast, Haskell’s late-night canvass, done via a telephone system with limited connections by one man, Brady – a member of the Ku Klux Klan with no official connection to the Secretary of State’s office – required only a few hours.

Just two years earlier, Haskell’s own election for governor generated more than 240,000 votes. But the Capital removal election – easily the most well-publicized and controversial state question in early Oklahoma history – somehow drew only about 160,000, a reduction of more than 80,000 votes, all of which were counted in a single, five-hour period.

Documents from the 1908 petition to move capital show that it took state officials a full month – from November 3, 1908 to December 3, 1908 to canvass and certify that election. Unlike Haskell’s late-night four-hour canvass of the 1911 vote.

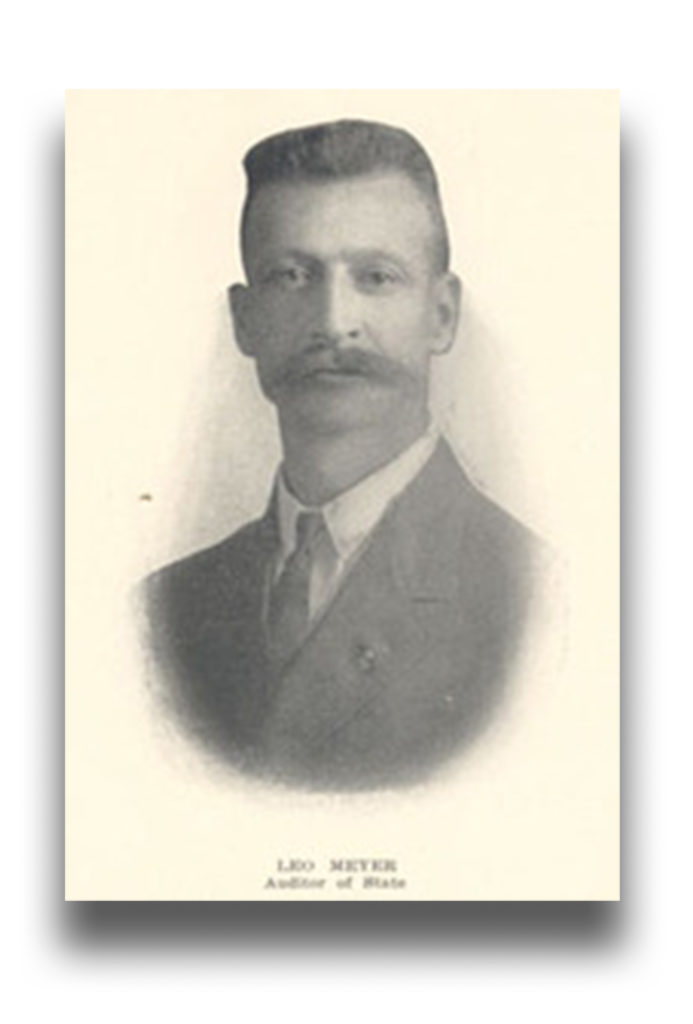

In fact, at least one historian said the 1911 vote was never officially canvassed, though documents from the archives of the Oklahoma State Election Board do show recorded votes of each county. Secretary of State Bill Cross, Meyer said, was in charge of gathering the election returns.

Even the fabled Associated Press questioned the validity of the removal election, in a sketch of Haskell prepared shortly before his death: “One of the sensational events connected with Haskell administration was the unauthorized moving of the state capitol from Guthrie to Oklahoma City,” the news service wrote in 1930.

“Haskell thought that the capitol should be in the latter place, so, while the matter was still unsettled, he put the great seal of the state and a few records in his suit case, got, in an automobile, and moved the capitol to Oklahoma City, establishing himself temporarily in a downtown hotel.”

Despite the AP’s erroneous claim that Haskell moved the seal by himself in a suitcase, its assertation the Capital’s move was ‘unauthorized’ and ‘unsettled’ lend bulk to the argument that illegal methods were used to shift the seat of government from Guthrie to Oklahoma City.

Once the election was over, Haskell moved quickly.

Using his influence to secure a special train to the Oklahoma City, the governor and his party left Tulsa just after midnight. By the time Haskell arrived in Oklahoma City, the third act of his drama was under way.

Before the sun rose on Sunday, Haskell issued yet another command that, over the course of Oklahoma history, has become legendary. Just prior to leaving Tulsa, Haskell called his private secretary, W.B. Anthony and told Anthony to get the official state seal and come to the Lee-Huckins Hotel in Oklahoma City, early Sunday morning.

The conversation, recorded by a former State Democratic Committee Chairman Fred P. Branson — who would later serve on the Oklahoma Supreme Court — was retold later in the publication, The Chronicles of Oklahoma. Branson, who was with Haskell and his wife in Tulsa, said Haskell immediately began taking actions to remove the Capital – acting without properly canvassed or certified election returns.

“Bill, this is Haskell,” the governor said in a phone call to Anthony. “I have been phoning over the state and find that Oklahoma City has won the capital fight. Get hold of Bill Cross, Secretary of State. Go up to the Logan County Court House, get the seal of state and bring it to Oklahoma City and meet me there in the morning by 7:30. Don’t fail to get the seal, Bill, and bring it to Oklahoma City.”

Anthony, who had traveled to his home in Marlow to vote, complied. From Marlow, he went to Oklahoma City and, following Haskell’s telephone call, drove on to Guthrie. Once in Guthrie Anthony, along with Earl Keys an employee of Cross’ office, and Paul Nesbitt, the governor’s chief clerk, went to the Logan County Courthouse – where Haskell’s office was located.

The four men arrived at the courthouse around 3 a.m. Sunday and were stopped at the entrance by night watchman Dooley Williamson. Anthony told Williamson that he and the other men were there to retrieve Anthony’s laundry.

“I had left of bundle of laundry in the governor’s office and a few articles of clothing,” Anthony said. Williamson let the men enter the building. Using the laundry bundle as cover, the trio gathered the state seal and its recording book and, wrapping them in the laundry “removed them from the building to my room without anyone except the principals ever knowing what was going on.”

Here again, the actions of Haskell, Anthony and others indicate a previously-developed plan, conceived before the June election took place. Further, long before Haskell placed his telephone call, Cross had already telephoned Keys and Meyer, both employees of the Secretary of State’s office, and told them to meet Anthony at his room in Guthrie and “do what I would tell him to do.”

Keys told journalists that Cross had telephoned him “about 7 p.m. advising that Anthony would be in Guthrie about 11 p.m. with a message from me to him and told me to do what the message requested.”

Cross’ telephone call to Keys was made at 7 p.m. on the Saturday of the vote. The timing of the telephone call shows the plan for the Capital’s removal was already being executed at the same time the election was taking place, another indication the men involved had advance knowledge of how the election would end.

About 11 p.m. Saturday night, Keys said Cross telephoned again. In that phone call, Cross told Keys that Anthony had been delayed but when Anthony did arrive in Guthrie, he would contact Keys at his home.

Early Sunday morning Anthony called Keys for the third time. “He said, ‘Earl this is Bill Anthony, can you come down to your office?’” Keys said. “I dressed, walked down to the courthouse on East Harrison Avenue and in front of the courthouse I saw a Cadillac touring car.”

Anthony, Keys and the others talked their way past the courthouse guards, wrapped the seal in a bundle of clothes and drove to Oklahoma City.

Like the petition and Haskell’s alleged vote canvass, the story of the seal’s removal has raised far more questions than answers and has, over time, become the primary answer to why the Capital was moved from Guthrie to Oklahoma City.

•

Still, questions remain. For example:

- How did Anthony just happen to have immediate access to a car and driver provided by the Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce at 3 a.m. on a Sunday morning?

- Why was Anothony’s laundry and clothing were conveniently left in the governor’s office?

- If Anthony and others were acting legally why did they fear violence?

Anthony told several newspapers that he and the others traveled in the chamber’s car to Oklahoma City to meet the governor. “We left Guthrie about four o’clock and arrived in Oklahoma City at about seven o’clock on Sunday morning,” Anthony said, “in what was altogether a very uneventful trip.”

But that trip Meyer, the Assistant Secretary of State said in 1933, didn’t have to be made. According to Meyer, the Great Seal of Oklahoma was already in Oklahoma City.

Because the whole scam had been pre-planned, Meyer said he took the biggest of the three state seals and placed it in the vault of the Lee-Huckins hotel on Saturday morning, the day of the election. Instead of being ‘stolen in the night’ one of the State Seals, it seems, had been unceremoniously waiting for the governor in the vault at his Oklahoma City hotel a full day before Haskell arrived.

Meyer said he made the ‘deposit’ when he traveled from Guthrie to Sayer to vote.

“We had three state seals,” Meyer said, “a large one, which we called the Great Seal and two smaller ones. One of the small ones was kept in my home, as I was called upon to attest documents at all hours and times. On the day of the election, before I left Guthrie to go to Sayer to vote, I took the Great Seal with me and left it in the vault of the Lee-Huckins while passing through.”

In his interview with the Federal Theater Project, Meyer said he left a note for Haskell, telling the governor the Great Seal had been placed the hotel’s vault. “He did not get the note before he left for Muskogee,” Meyer said. “If he had he would not have sent his private secretary, Mr. Anthony, to Guthrie to get the seal.”

The result was that Anthony’s men didn’t need to smuggle a seal out of Guthrie; one had already been taken to Oklahoma City.

Meyer said that Haskell and this kitchen cabinet “felt pretty sure” that Oklahoma City would win long before the election occurred. Because of this belief, or perhaps because of advance knowledge of how the vote would turnout, Meyer said he made arrangements several days earlier with the manager of the Lee-Huckins hotel for rooms to be used by the Governor and the Secretary of State.

By 7:30 a.m. Sunday Haskell, now safely ensconced with friends and supporters at the Lee-Huckins, ran his next play. Using the ‘election returns’ gathered for him by Brady, Haskell took a piece of hotel stationery, flipped it over and began writing a proclamation that moved the seat of government from Guthrie to Oklahoma City.

After he signed the proclamation and Cross affixed the seal, Haskell hung a hand-written sign on a door of the hotel that said, “Governor’s Office.”

But just as before, Haskell’s actions drew scrutiny.

At least one member of the Oklahoma Supreme Court, who was at the hotel with Haskell, questioned the governor’s authority to move the seat of government. According to Oscar Presley Fowler’s 1933 book, The Haskell Regime, “one of the (state’s) supreme court judges was severely distressed” by Haskell’s proclamation to move the seat of government.

A story, published in the Los Angeles Times on Monday, June 13, 1910, indicates that the Supreme Court justice who raised the concerns was probably Samuel Hayes, who was with Haskell, Lt. Governor George W. Bellamy, Cross, State Auditor Martin E. Trapp, and State Labor Commissioner Charles A. Daugherty that morning in Oklahoma City.

“C.N.,” Justice (Hayes) said to the governor, “have you looked into this matter? Can you legally issue the proclamation before the election returns are in?”

Haskell replied that he could. “The law authorizes the governor to issue the proclamation moving the Capital when he is satisfied that the city has received a majority,” he said. The official election returns, Haskell added, “are merely for a permanent record for posterity.”

Once the proclamation had been issued “a furor arose throughout the state,” Branson wrote, “as to whether or not this was legal action or whether it was prudent action.”

Following Haskell’s proclamation on Tuesday, Meyer, acting in his official role, prepared another document showing the results of the election – which still remained uncanvassed by state officials. But as the document was being readied, legal questions arose about where, exactly, it should be signed.

“We took it up with leading attorneys,” Meyer said. “It was suggested that as Guthrie was the Capital until the proclamation was signed, that the governor and I should go back there and sign it.”

Meyer said he and Haskell took the Santa Fe train back to Guthrie. Meyer was in possession of the Great Seal, briefly returning the seal to Guthrie. “The governor and I signed the proclamation in the Harvey Eating House in Guthrie,” he said. “I attested it with the seal, and we got on the train, which left a few minutes later for Oklahoma City.”

Here again the governor’s own actions – concern that the proclamation would not be legal unless it was signed in Guthrie – underscore the fact the capital had not been legally removed, despite his efforts.

Meyer said Haskell sought the council of ‘the leading attorneys’ who made the case the capital was still legally located in Guthrie — despite the governor’s late night efforts.

The election and Haskell’s abrupt action to establish Oklahoma City as the seat of state government were on thin legal ground, the attorneys said, unless the governor signed and sealed the documents in Guthrie – which still remained the legal state capital.

Within hours, news of the move spread like wildfire. The Daily Oklahoman hit the streets with a special edition, and attorneys in Guthrie filed a suit in Logan County District Court challenging the validity of the election.

In an interview published in the Guthrie Daily Leader on June 14, Haskell said the capital of Oklahoma “is constructively at Oklahoma City.” He also dismissed the need to bring state records with him. “We don’t care for the records and the records will not be moved from Guthrie yet – perhaps never,” the governor said. “The State Capital is constitutionally at Oklahoma City. There is no law to compel a white man to live in the same town with Frank Greer.”

Questioned about fluctuations in election returns, Haskell told the newspaper “he hadn’t kept up with them,” in spite of his earlier statement claiming to know the election’s totals.

Those questions, coupled with the fact that Haskell had previously conspired with others – according to Meyer – to prevent the removal petition from being publicly known until the protest period had expired, put the validity of the 1910 election and Haskell’s actions as governor in doubt.

Haskell, it seemed, had succeeded. The seat of government had been moved from Guthrie to Oklahoma City.

But the fight to keep the capital in Oklahoma City was far from over. By Monday, the capitol removal effort had become an all-out war.

In Guthrie, near Main Street, residents hung the governor in effigy.

Up next: Guthrie turns to the courts as Haskell doubles down