Bart Banfield Says Epic Will Change And Thrive

OKLAHOMA CITY — The past two years, have been the most difficult time in Bart Banfield’s professional career. His job, he said, featured a daily barrage of ugly news stories, investigations, social media hate messages and threats.

The negative atmosphere was overwhelming.

But Banfield, the superintendent of Epic Charter Schools refused to quit and, instead, focused on solving problems and restoring the public’s faith in his school. To do that, he relied on his faith in the Almighty and the lessons he learned from basketball.

But he needs more time.

•

As a kid, Banfield was all about basketball.

Banfield’s father Bob, a coach, encouraged athletics. “I was in the gym with a basketball in my hands at a young age,” he said. “I spent hours and hours there.”

Those lessons — teamwork, leadership, strategy and understanding how to lose with grace — would become very useful later his career.

“I grew up with a basketball in my hand basically since I was born,” he said in a 2019 media statement. “These are lessons that, when you’re going through them, can be painful at the time, but later on in life, you realize that becomes the foundation on which you live your life.”

A product of Oklahoma’s public schools, Banfield said he didn’t plan on being a school superintendent. Instead, his goal was simple: become a basketball coach like his father.

Fate, however, had other plans.

Banfield’s academic mentor, Ray Cooper, encouraged him to pursue a master’s degree. “He told me I’d be a good leader,” Banfield said. “I thought he was crazy. I was gonna coach for the rest of my life.”

But Banfield did follow Cooper’s advice. A year later, he began the master’s program at the East Central University in Ada — all while teaching, coaching basketball and raising a family. He would continue that way for five years.

That is, until Stidham called.

Armed with a fresh degree and five years of experience, Banfield moved his family to the small rural school district of Stidham, in southeastern Oklahoma. Named its new superintendent, Banfield quickly earned a doctorate-level education in how to run a public school in Oklahoma.

“At Stidham I got to do everything. I even drove the bus. I gained a great deal of experience really quick,” he said.

The challenge that faced him, though, was the district — a small dependent school district with no high school– was surrounded by cattle. Growth was limited.

And enrollment at Stidham was declining.

By his second year, enrollment had dropped so much that Banfield knew if he didn’t take action quickly, things would get ugly. He couldn’t afford to lose any more students.

So he decided to try something different.

Leveraging and idea he’d gathered from Angus King, the former Governor of Maine, Banfield shifted the school to one-to-one learning with technology. He developed a program similar to King’s Maine Learning Technology Initiative.

King’s program, launched in 2002, provided learning technology for every 7th through 12th grade public school student. Maine’s program was one of the first in the world and the first in the country.

For Banfield, the idea was a game changer.

“We were trying to figure out how to attract students to our school,” he said, “so we embraced technology and a one-to-one learning environment.” Banfield equipped each student in the district with a laptop and internet access. He moved away from what he called the industrial style of education to a system that used technology and focused on the student.

“There was a generational gap (with technology),” he said. “Most of the leaders of public schools, even today, are in their 50s, 60s and 70s. Here’s this 27-year-old that’s coming in and there was a generational difference. They didn’t understand or really appreciate the role that technology could play educating the child. I was young enough to appreciate and respect the role technology could play. And so, we did it.”

Banfield said the change was dramatic.

In addition to state and national exposure, Stidham’s new approach to education increased test scores and reduced discipline problems. “People were coming to Stidham, Oklahoma to talk about this crazy school that had invested in technology and was educating kids in a different way, something that had never been seen before. All of the sudden we started to attract kids from other schools.”

By 2008, Stidham was offering middle school students public school credit for classes taken online. Banfield and his small school were now seen as cutting edge, but the use of technology made the young superintendent an outlier in Oklahoma education.

“We were experimenting at the time. The internet was still kinda new. What we began to do was understand the role that technology could play,” he said. “And what we figured out was the future of learning was blended.”

Those ideas would lead Banfield to Epic.

•

In July of 2013, Banfield — now the state’s youngest public school superintendent — met Ben Harris and David Chaney. The trio met after Banfield gave a speech about his use of technology at a state teaching conference.

While Banfield’s unique program at Stidham had brought state and national attention to the small rural school district, Chaney and Harris had launched their own charter school, Epic, modeled on a similar concept.

Banfield said he was impressed by the pair’s approach to education. He was so impressed that he wanted to partner with Epic and expand his blended learning model. “At that time, they were interested in blended learning. They were already doing virtual. What they wanted to do was blended learning centers and I approached them about forming a partnership with Stidham.”

That didn’t happen. Instead, Chaney and Harris offered him a job.

“We met in Bricktown,” Banfield said. “What was supposed to be a one-hour meeting turned into a three-hour meeting. Ben and David told me that if I wanted to do a partnership with my small rural school, they would do that, but they were really interested in me coming to work for them,” he said.

Banfield was drawn Epic because of its use of technology and its one-to-open approach to education. In January of 2014 he left Stidham and joined Epic as an assistant superintendent.

“It was a risk. It was a start-up,” he said. “And it was different.”

Banfield said he chose to come to Epic because he felt deep down that Epic had potential and could possibly help tens of thousands of students across the state.

Still, he knew the school – which he still describes as one of the most innovative in the state – would be criticized. “From day one Epic has been polarizing,” he said. “And typically, most people fall into one of two buckets, you either love it or you hate it – but the last two years have been the most challenging for us.”

Those seven years haven’t been easy.

Banfield had only been at Epic a few months when he faced his first major challenge – addressing new rule adopted by the Statewide Virtual Charter School Board. That rule limited the amount of time an Epic one-to-one teacher could spend with a student.

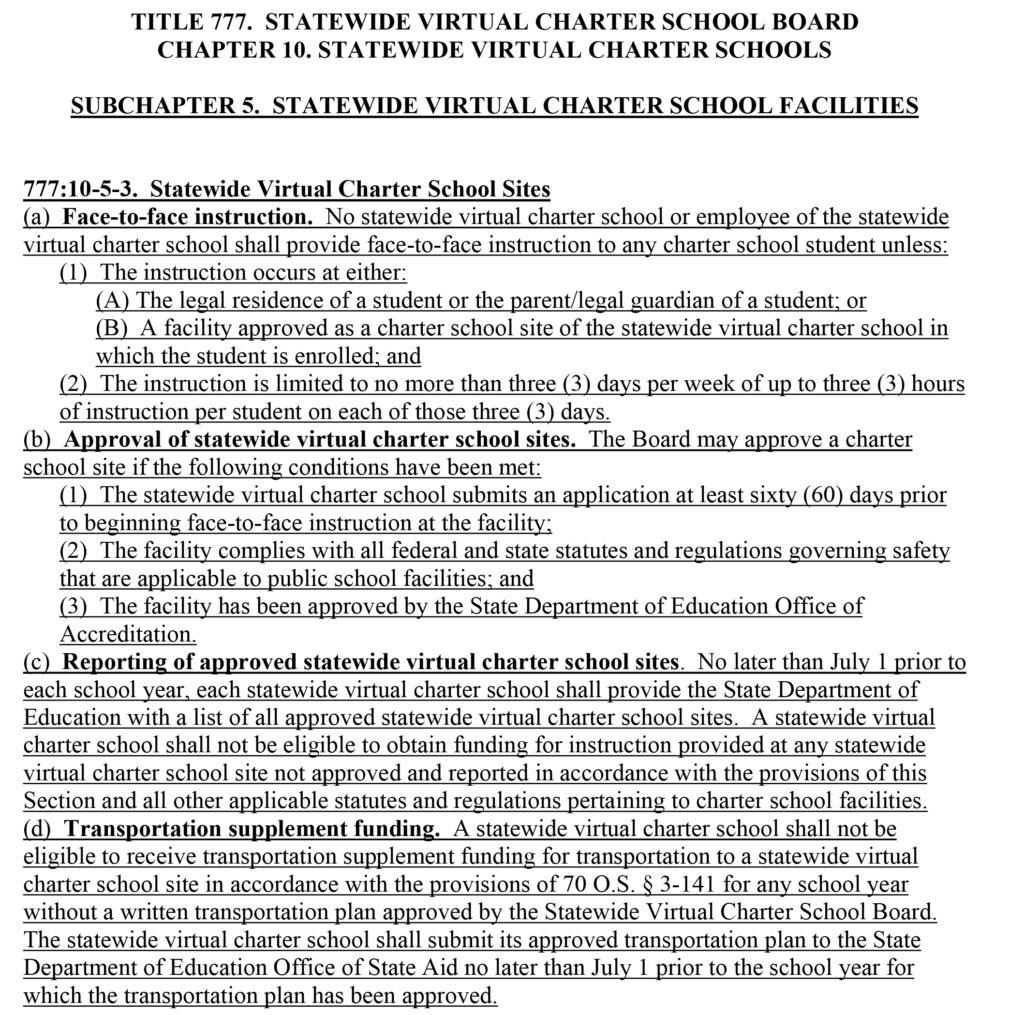

Authored by then-SVCSB chairman John Harrington and championed by then-Governor Mary Fallin, the rule limited student instruction by teachers who used the virtual platform.

“The instruction is limited to no more than three days per week of up to three hours of instruction per student on each of those three days,” the rule said.

A rule impact statement published at the time said the rule was necessary “to clarify the circumstances under which a statewide virtual charter school may provide face-to-face instruction to enrolled students and to ensure that facilities at which statewide virtual charter schools may provide in person instruction to enrolled students are safe environments for students.”

The SVCSB said the rule was also necessary to clarify the requirements for obtaining funding for transport of children to statewide virtual charter school facilities in the unique full-time virtual charter school environment.

The rule – which would be overturned a few years later – would spark Epic’s creation of its Tulsa and Midwest City Blended Learning Centers.

Now with two districts – a virtual district and a district that operated blended learning centers in Tulsa and Oklahoma City – Epic began to grow, quickly outpacing Oklahoma’s larger brick and motor schools.

Then all hell broke loose.

•

By the summer of 2019 Epic, its founders and its leadership team were under fire from media across the state. The school was accused of fudging enrollment numbers and breaking state law by allowing students to participate in programs through its Learning Fund that did not have a state certified teachers.

In addition, an investigator with the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation sought court approval to confiscate a laptop and cellphone used by an Epic teacher. The controversy generated stories for months and caused Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt to ask the State Auditor’s office to conduct an investigative audit of Epic’s finances.

That fall, Banfield said, felt like a fight. “When you are under assault my multiple state agencies, and critics and detractors and media, you know it becomes very difficult to discern who you can trust. I could feel our circle becoming smaller and smaller.”

By mid 2020, Epic’s rapid growth – now pushed in a large part by the COVID-19 pandemic – would eventually take its enrollment to more than 61,000 students. The change, the millions in additional state funding now earmarked for the school, and the controversy surrounding Epic’s founders and their company, EYS, generated additional criticism, scrutiny and debate.

Much of that criticism surrounded Epic Youth Services and the way it managed Epic’s Learning Fund, a program that earmarked each family a $1000 credit to purchase extracurricular activities. Because the program was managed by EYS, a private entity, company officials wanted to keep Learning Fund records private. Critics countered that the funds paid into the program were state dollars and therefore public records.

In October, State Auditor and Inspector Cindy Byrd release her audit of Epic. A short time late the SVCSB voted to terminate Epic’s contract — a move that would have shut down the school.

“It was a time filled with doubt and the very existence of school called into question,” Banfield said during a meeting with Epic administrators in June. “The choice to make was clear. If we were to continue as a school at all dramatic, meaningful and profound changes had to be made. These threats to our existence were very real.”

Epic officials went into full crisis management mode.

For Banfield, the fallout from the forensic audit, the OSBI investigation and the onslaught of negative press made 2019 and 2020 ” the most difficult two years” of his professional career. But that same controversy, he said, also sparked positive change at Epic and within its leadership.

“When the audit report was released in October you had two choices: One, you can sweep it under the rug and perpetuate a paranoid mentality that says, ‘everyone is out to get us’ or you can choose to listen. And I believe that leaders are listeners first.”

That audit, he said, forced Epic and its leadership to “take a long, hard look in the mirror and realize that we had some areas that we needed to improve.”

Since then the school has undergone dramatic changes which have been praised by both Epic’s supporters and its critics. In addition to new rules requiring greater transparency, Epic’s school board moved the Learning Fund away from EYS and under the school – making all fund records public documents. The board also severed ties with Chaney and Harris and with EYS.

Now fully non-profit, Banfield told his administrators that Epic will save $40 million — that would have been paid to EYS as management fees. He said the school will now have superior technology and administrators will be able to streamline operations and innovate in new ways.

“We are no longer a top-down organization,” he said. “We are going to have great resources.”

Still, many challenges remain.

The school and the SVCSB continue to debate whether Epic needs two separate boards of education with different individuals on each board. A grand jury investigation continues, a second audit by the State Auditor and Inspector is being conducted and several lawsuits remain pending.

But Banfield believes Epic’s future is bright.

“We want to get back to the basics,” he said, “teaching and reteaching these Oklahoman academic standards.”

To get there, he said Epic will continue its virtual, one-to-one school but also push for more face-to-face instructional time and for the development of more blended learning centers or micro schools with a student population of 250 students or less.

The educational model at its core, Banfield said, is face to face.

“Kids need face to face,” he said. “That time with the kid is essential in order for us to bridge that gap. I think we have to be very careful as a state and as a nation that we are not focused on quantity but quality.”

•

Epic’s future success, he said, will require teamwork and dedication – the same tools required of his basketball teams.

But this is no basketball game.

Banfield and his team have to do more than just win – they have to change the perception of Epic as a public school and, at the same time, improve academic outcomes and properly educate thousands of Oklahoma students.

“We have to get this right,” he said.

He also has to change attitudes inside the school.

“It’s not going to happen overnight,” he said. “But I think the end result is something that everyone will be proud of when it’s all said and done.”

Banfield said part of the reason Epic continues to be the state’s fastest growing public school district is that it has an incredibly talented workforce, and its teachers understand that educating a child is more than just a test score.

“We’ve got a school full of kids who are behind credit, below grade level, at risk,” he said. “What those kids need, immediately, has nothing to do with academics. What they need is support. What they need is love. What they need is an advocate. That’s what we provide. We’ll get to the science part, but we have to start with the art of teaching. If you get a child to buy in and to believe. They will move mountains. That’s what we do. One kid at a time.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: The Epic News Network is a journalism program funded and supported by Epic Charter Schools. Cover photo by ENN photographer Bekah Disney. Videos by Phil Cross.